| Policy |  |

Renewable energy policy framework

International policy context European Policy context National policy context

Scottish policy context Future Recommendations References

International policy context

The main driver for development of renewable technologies has arisen from the requirement to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. The UN Earth Summit of 1992 in Rio de Janeiro established the need to control greenhouse gases due to concerns over increasing levels of global warming and pollution. Following on from this the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, aimed to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases by the developed nations, which in turn led to widespread support for the development, and deployment of electricity generated from renewable resources.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has now established a new Implementing Agreement on Ocean Energy, focusing on wave energy and marine currents, as a "result of the importance of these energy resources."

back to top

European policy context

In response to international agreements such as Kyoto, the EC agreed to tackle its greenhouse gas emission problems in two main ways, firstly it agreed that the source of pollution should be minimised to as low a level as was economically possible. Secondly, as a major source of greenhouse gas emissions is the electricity generation industry, all member states committed themselves to increasing the contribution to energy supplies from renewable means. This was achieved by EU Directive 2002/358/CE, published towards the end of 2001 which required member states to set levels and targets for reducing emissions as well as increasing renewable energy supply.

back to top

National policy context

At the start of 2003, the UK Government released its energy white paper "Our Energy Future" promoting the reduction of the UK’s carbon dioxide emissions by 60% by around 2050. It committed itself to supplying 10% of national energy needs from renewable sources by 2010 and set an additional goal of generation of 20% of electricity from renewables by 2020.

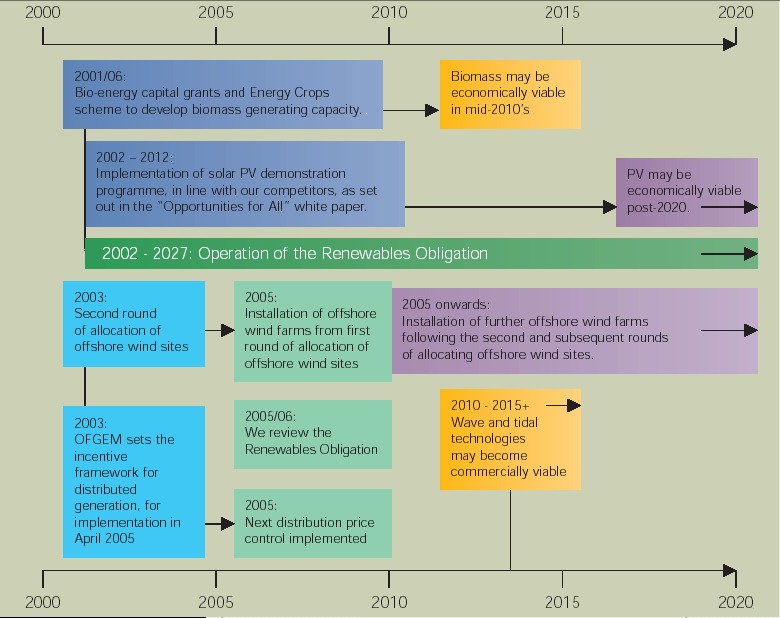

In this white paper, the government envisaged tidal technology becoming commercially viable by 2010 (see renewables timeline below). It states that "...wave and tidal [energy] are further off but potentially very important..." The document stresses the importance of giving wave and tidal technology the opportunity to play a major part in future generation.

Specific investigations into the potential marine resource have been prompted as a result of these priorities:

- The report from the "House of Lords European Communities Committee" on "Electricity from Renewables - 1999" raised questions about the lack of progress in the investigation of energy from tidal streams.

- In the same year, the "Report of the Marine Foresight Panel's Energies from the Sea Task Force" reinforced the potential of wave and tidal energy to supply a major portion of Britain's energy.

- The Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution's report on "Energy - the Changing Climate - 2000" recommended stronger government support for tidal energy.

- The Seventh Report of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee on "Wave and Tidal Energy" in 2001 outlined the "enormous potential advantages of wave and tidal technology as sources of energy" and stated "we can no longer afford to neglect the potential of wave and tidal energy".

back to top

Scottish policy context

The Scottish Executive has devolved responsibility for the promotion of renewables in Scotland as well as the consents required under Section 36 of the Electricity Act to construct and operate both on and offshore generating stations. It has committed itself to raising the overall proportion of electricity generated in Scotland from renewable sources to 18% by 2010 with the hope of extending this further still to perhaps as much as 40% by 2020.

back to top

Future recommendations

- Support within existing Incentives (Scottish Renewables Order and Fossil fuel Levy) for new energy sources such as tidal.

- Attract large scale capital investment to assist with Grid Connectivity

- Stimulate Research and Development

Allowing fine tuning of existing incentives such as the Scottish Renewables Order and the Fossil Fuel Levy in order to support more-expensive less-developed energy sources such as marine current energy in attracting investment will encourage diversity of supply. For example, the existing SRO mechanism leads to the lowest cost option being adopted (wind).

The sites with the lowest unit costs for large scale wind wave and tidal generation stations are generally not close to the point of consumption. Extension of the grid in terms of reach and capacity will be necessary (see grid connection section).

Long term, the most efficient mechanism may be for the generators to bear the proportion of the transmission costs required to distribute their products, but in the short term the Government may need to encourage particular grid expansion ahead of demand to stimulate specific developments.

A subsidy could be used for shortfall in transmission revenues up to a break even point. This would reduce risk for investors, but then tail off as the new renewable generation stations came online.

Government commitment for Grid Extensions to key tidal sites such as the Pentland Firth would be key in stimulating the development of a network of generating installations large enough to achieve economies of scale.

Scotland should aim for a `culture of innovation' in order to become leaders in the Tidal Flow energy sector.

Full-scale trials can be encouraged at favourable tidal sites. The UK has the advantage that it's tidal stream sites are a unique resource not so easily available to the EC competitors. Scotland has strong skills in offshore operations and manufacturing, that can be promoted to business, alongside direct grants, high quality facilities (including academic links), regulatory commitment and intelligent planning.

A licence scheme could be used to stimulate trials at favourable sites. The ideal tidal flow sites are limited to specific locations, and as the number of these is limited, the government could ensure proper use of these locations through a licensing scheme (similar to that used in the oil and gas industry in UK territorial waters). The prospective licence holder would have to submit a work programme with their application. If this was approved, the company would have to reach set stages of development or they would forfeit the licence, which would then be allocated to another operator. The option to exploit one of a limited number of favourable tidal sites for a period of 20 or 30 years would potentially be very valuable to the new energy companies, and the capability to set milestones for the development of the renewable resources would be valuable to the Government.

Options to direct profits into investment through tax relief on energy supply profits could be offered to prototype and full scale installations. These would lower the hurdles to tidal stream development and add pressure to reduce the time to bring installations online.

References

- Richard Boud, Future Energy Solutions for the International Energy Agency and DTI (2003),

Status and Research and Development Priorities 2003 – Wave and Marine Current Energy,

International Energy Agency.

- DTI (Nov 2002), Future Offshore – A Strategic Framework for the Offshore Wind Industry,

HMSO.

- Mr Robert Weir (10 February 2004), Submission to Renewable Energy in Scotland inquiry,

Enterprise and Culture Committee.

- Scottish Energy Environment Foundation (1 March 2001), Memorandum submitted to Government

Inquiry

-

Scottish Executive (2002), PAN 45 (revised 2002): Renewable Energy Technologies, Scottish Executive

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/library/pan/pan45-02.asp -

DTI (February 2003), Government White paper - Our Energy Future, HMSO.

http://www.dti.gov.uk/energy/whitepaper/index.shtml