Space Utilisation

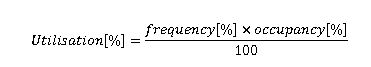

Space utilisation is the product of occupancy frequency (how often a space is occupied) and occupancy levels (how close to capacity a space is when it is occupied), expressed as a percentage:

Universities across the UK perform very poorly in space utilisation with a 27% average across the sector in 2006. This is due to an approximate score of 50% in both frequency and occupancy (SMG, 2006).

For improvements in utilisation there has to be an increase in space usage (frequency), space occupancy or both. This can be achieved by the use of flexible learning spaces, better space management policies or an increase in campus population.

Failing this, a decrease in the total space available on campus will result in the remaining space having a higher utilisation rate. The remaining spaces take the occupancy load of the spaces that are vacated. This can be an attractive option for increasing utilisation while reducing carbon emissions. Removing poor performing, general purpose or outdated buildings means that these buildings no longer need heating or electricity supplied to them.

Space and Strathclyde: reducing campus size

For the case study of the University of Strathclyde, space utilisation is approximately 24%. The university has a target of a 40% utilisation rate, to be met by a mixture of downsizing the campus, more flexible office spaces and reduced departmental offices and spaces (University of Strathclyde, 2010).

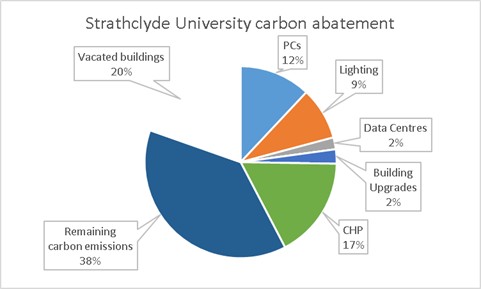

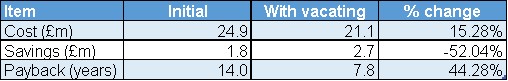

For the purposes of the project, it was assumed that some of the older teaching and administration buildings could be vacated (such as the Collins building, the Livingstone Tower and the Graham Hills building) for a total campus area reduction of 24%. This equates to a carbon saving of 20% from baseline emissions. After adding the other carbon reduction methods are applied to the remaining buildings on campus a total carbon reduction of 62% can be achieved (Figure a), compared to 50% without vacating buildings.

In addition to carbon reduction potential, the costs of campus improvements would be reduced by vacating buildings. The buildings selected for theoretical vacation cost £1.1m in gas and electricity to operate in 2014. They would not need fabric, HVAC or lighting upgrades and the CHP engine could be downsized to reflect the reduction in peak loads.

Key points

As can be seen from the above example of the University of Strathclyde, reducing campus footprint can make a significant contribution to meeting carbon reduction targets.

Vacating buildings is a very aggressive means of tackling energy use and space management. It forces change rather than encouraging it through better practice. For this reason it may be unpopular and difficult to implement on university campuses, especially at the scale in the above example.

A broader point on sustainability and building use: simply selling or vacating a poorly performing building fixes the problem of excessive energy use for the party selling (in this case a university). The building will still need to be improved to meet energy performance criteria if and when it is refurbished (DCLG, 2012) so the issue of it being a poor performer still stands.

References

SMG (2006) Space utilisation: practice, performance and guidance [pdf] Available at: http://www.smg.ac.uk/documents/utilisation.pdf (Accessed: 30 April 2016)

DCLG (2012) Recast of the Energy Performance of Buildings Regulations [pdf] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/39379/Impact_Assessment.pdf (Accessed: 30 April 2016)

University of Strathclyde (2010) Space Management Policy [pdf] Available at: https://www.strath.ac.uk/media/ps/estatesmanagement/policy/space_management_policy_valid_from_October_2010.pdf (Accessed: 30 April 2016)